Bonds are Boring...until they're exposed as the central suspect in multiple financial murders

My first "real" investment job was investing in bonds.

I wanted to be an equity investor, so I treated bonds that way. I found bonds that were just about to be upgraded by Moodys or S&P because their industries/companies were improving, and bought ahead of the upgrades, making money on the trades.

My boss was unimpressed. He was horrified.

"Emmy, our job is to invest premium to be able to pay claims. We are an insurance company. We BUY bonds. We don't trade them."

Next day, I found another poised to rally, bought it, then 1 month later, sold for a profit. I probably took 10 years off my boss' life.

At the time, I thought he was nuts, not wanting to make a profit.

Looking back, he had a point.

I joined Farmer's Insurance in 1994, right after a huge mortgage bond fiasco. Clever investment bankers had figured out how to separate principal and interest, and sold PO and IO bonds separately. Principal Only (PO) bonds held the allure of huge returns.

Insurance companies, including Farmers, bought a lot of PO bonds.

Then rates went up in early 1994, crushing the value of these long-bonds, and Farmers lost a fortune (reminiscent of SVB today).

The day I joined, those brilliant bond buyers at Farmers were still huddling and strategizing how to keep their jobs. So, what the head of the bond department wanted from me was simple bond buying.

History rhymes, in 2008, we suffered the Global Financial crisis when increasing rates caused reverberations through the bond markets, blowing up more newfangled securities investment bankers had dreamed up.

One of my most successful mentees went into bonds. He was a brilliant equity investor, yet, when it came time for me to advise him, I recommended getting into "boring bonds".

Why?

Credit cycles drive economic cycles. Know bonds and you can read the tea leaves for the economy, markets, and our collective financial future.

The global credit market is 2-3X the size of the equity market (more money), and less competitive. Most young people want to invest in stocks, not learn the intricacies of bonds.

It is pure math, and you can get better than others at complex math (he did), and dominate the space. My first boss, Mike Milken, was a billionaire in the 1980s doing just that (and some other things that landed him in jail, um "camp" for a short stint).

All of us, no matter our careers, can benefit from understanding of bonds.

Today's email has 3 parts:

(Not so boring) Bond Basics - why rates matter

Bonds' relation to the current banking crisis

You have the power to see the future

(Not so boring) Bond Basics - why rates matter

The cool, and sometimes not cool, thing about bonds is that they are simply an equation. I want to borrow money from you. You tell me you will loan me $1,000 for a year if I pay you back the full amount plus 5% interest. I don't have to pay you interest monthly, just at the end of the year.

If a correct interest rate for the cost of money and individual risk of loaning to me at 5%: $1000 today = $1050 in 1 year, and the bond is worth "par" or $1,000.

My financial situation immediately worsens, and the market crashes, such that 10% is a better interest rate the next day (keeping it simple so t remains at one year).

Original Bond Value = Face Value ($1,000)/(1+r)t

V = $1,000/1.05 = $952 (present value of getting back $1,000 in a year)

Interest rate changes to 10%

V = $1000/1.10 = $909 (value goes down 5%)

Now, what happened with those SVB long bonds?

SVB had 30 year treasury bonds, so the value moves far more, offset by the interim coupon payments. Duration is the length the bond would be if it were a zero coupon bond, ie without the interim payments, so you can compare apples to apples.

Think about your own mortgage. High or low interest rate? Variable? Lump sum at the end? The way for markets to compare all of these against each other is duration.

Currently the duration of a 30 year treasury bond is 11 years.

One wrinkle is duration changes with risk and rates, but we will leave that out.

SVB had the equivalent of 11 year zero coupon bonds in their portfolio.

Yields on the 10 year treasury (closest to 11 year duration) went from 0.536% in July 2020 to 3.91% in late Feb 2023.

Original Bond Value = Face Value ($1,000)/(1+r)t

Interest rate starts at 0.536%

V = $1,000/(1.00536)^11 = $943

Interest rate changes to 3.91% (still seems low, but that's a 7X increase)

V = $1000/(1.0391)^11 = $656

The value of SVB's portfolio of SAFE BORING BONDS went down by 30%

Here's the kicker: if SVB could have held them to maturity, for the 30 years, they would have been made whole. But they were investing with a duration of 11 years while their clients are fast and furious startups which have much shorter boom and bust cycles.

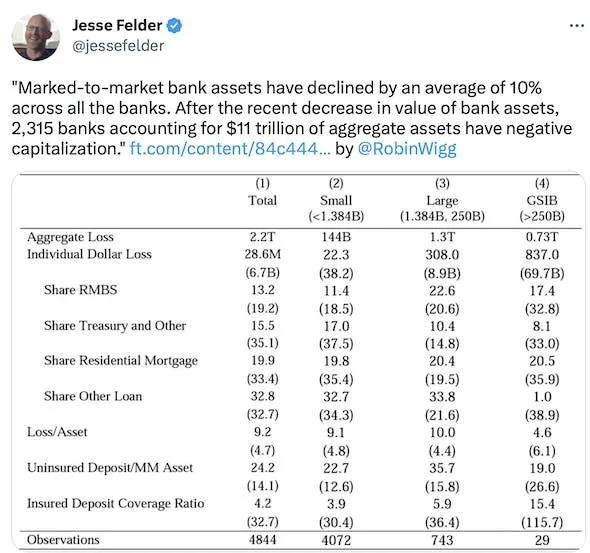

While all banks are not SVB, ie they have less volatile customers and didn't take a huge bet on long bonds at the wrong time, overall, rising rates has hurt banks' bond portfolios:

RISK, Bonds and the current banking crisis

Bonds are about math. Rates go up, bonds go down.

One thing I left out of the simple bond equation? RISK

Original Bond Value = Face Value ($1,000)/(1+r)t

r = interest rate, but that interest rate includes implied risk. When life gets riskier, you have to pay higher interest to get people to loan the same money to you.

Risk is embedded into the interest rate: (1) the day you get a loan and (2) every day those bonds trade.

Risk embedded into the interest rate is re-evaluated and re-priced daily as bonds trade. In fact, the massive volume of bonds trading daily, based on changing risks is what moves interest rates, not the Fed.

Enter the Bond Vigilantes!

A bond vigilante is a bond trader who threatens to sell, or actually sells, a large amount of bonds to protest or signal distaste with policies of the issuer. Selling bonds depresses their prices, pushing interest rates up and making it more costly for the issuer to borrow. - Investopedia

Bond vigilantes' power comes from the simplicity of the bond price calculation. Sell a bunch of bonds, prices go down and rates go up for those bonds. The vigilante part comes from a disagreement on implied risk.

I've written about the most striking Bond Vigilante, George Soros' bet against the British Pound, which broke the pound and made Soros billions. He "broke" the pound, or the level at which the UK government thought the pound should trade at, via the bond market.

With the US being at the center of the banking crisis, and the potential that these last two weeks are akin to April 2008, ie the collapse of Bear Stearns, which was followed by the August failure and rescue of AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and September 2008 bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers...

We may just be getting started.

Given the massive amounts of debt the US government accumulated over COVID period, there is a not-insignificant risk that the bond vigilantes come for the US (dollar and interest rates) the way George Soros came for the UK. Then what?

It's not that policymakers do a particularly great job, but when bond vigilantes do things like "break the pound", on the one hand, that is capitalism at work, but on a basic level, it becomes clear to all that Wall Street financiers have taken control and the Fed has lost control over basic economic mechanisms like the value of the US Dollar and the level of interest rates. In times when governments lose control to bond vigilantes, risk and uncertainty spiral up quickly.

You have more insights than you think

Rates go up enough, and people like you and me find it worth our time to move money out of our checking account into a money market account. Probably not worth it to earn 1% vs 0.5%. But 5% nearly risk free in a 1 year CD vs keeping it in a volatile and down-trending stock market or earning zero in our checking account? Sign me up!

Just as bond values were going down and banks needed deposits more than ever, people were withdrawing their money.

Startups withdrew because they were burning cash and not raising new rounds.

Individuals withdrew because they found better options.

Schwab stated that their clients moved $8.8 BILLION out of prime money market accounts (that invest in commercial paper) and moved $14 BILLION into government and treasury money market funds all in a THREE DAY period. This is what panic looks like.

And banks went into a deposit crisis. And fast. Want to see what a crisis looks like, plain and simple. It starts with "Things that make you go HUH."

What's wrong with this picture?

We should get paid more to lock our money up for LONGER. Banks are so desperate for money NOW, they all are offering higher rates for shorter time periods.

Banks also may be betting that rates will come back down, so they don't want to lock themselves into higher rates, but this is a HIGHLY unusual situation that you can take advantage of.

Rather than predict the stock price or whether this is like Bear Stearns which was in April 2008, then AIG, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac in August, then Lehman in September... rather than try and predict whether we are at the bottom of financial panic right now (something tells me we may not be), you can invest in 9 month CDs in financially strong banks. Not investment advice, but this is what many of my smart friends are doing.